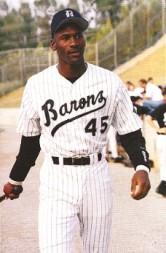

Over at Boston.com’s “Extra Bases” blog, there were over 50 comments on Monday from fans reacting to all of this Manny business. A few of them accused Manny of being a bad role model for kids. For example, here’s what commenter “Paul W.” wrote:

from fans reacting to all of this Manny business. A few of them accused Manny of being a bad role model for kids. For example, here’s what commenter “Paul W.” wrote:

“When I tell my little leaguers to model themselves after a major leaguer, I leave off Manny. I don’t want my players to think that selfish behavior is a positive attribute for a team. Follow Varitek, Pedroia, Schilling, or Beckett’s example, even Jeter’s or Posada’s. Any of these guys because they love and respect the game. But never Manny.”

I’ve taught middle school and coached a total of about 30 youth sports teams over the years, and I know where Paul W. is coming from. Yes, in ONE obvious way, Manny’s approach to the game of baseball is not what I would teach my young players. His obvious flaw is that, frequently (but not always), he fails to sprint down the first base line as soon as he has hit the ball. Sometimes, he hangs out in the batter’s box and admires the ball he has just hit, and sometimes he runs at less than 100%. This isn’t OK in the majors, but it’s a cardinal sin in little league. (I know that Paul W. is also referring to Manny’s alleged lack of “team spirit,” but no matter how confident sportswriters and fans are about the details of this most recent story about Manny’s knee, we don’t know the whole story).

Yup, Manny loafs sometimes. Yup, that can be maddening and costly. However, in many ways, Manny sets a positive example for young baseball players. Here’s what I would say to players on my youth baseball teams about what to emulate about Manny Ramirez.

1. He approaches every at-bat with a clear mind. Manny’s not thinking about his last plate appearance and he’s not thinking about his latest gaffe in the field. He’s not even thinking about his contract and what his agent, Scott Boras, wants him to do. No, Manny leaves that all behind when he strides towards the batter’s box. He’s in his own MannyZone, and he’s thinking about two things: seeing a strike, and hammering it. Even with two strikes, Manny’s focus is unbelievable.

2. He expects to get a hit, every at-bat. The way Manny walks to the plate with an air of self-confidence, settles into the batter’s box, taps the plate with his bat, assumes his regal batting stance, and stares out at the pitcher… everyone in the park knows he’s already envisioned the line drive that he’s about to smash. This summer, my co-coaches and I taught our eight year-old players to chant the words, “I crush balls in the strike zone,” while standing in the on-deck circle and stepping into the batter’s box. Why? We were teaching them to think like Manny.

2. He expects to get a hit, every at-bat. The way Manny walks to the plate with an air of self-confidence, settles into the batter’s box, taps the plate with his bat, assumes his regal batting stance, and stares out at the pitcher… everyone in the park knows he’s already envisioned the line drive that he’s about to smash. This summer, my co-coaches and I taught our eight year-old players to chant the words, “I crush balls in the strike zone,” while standing in the on-deck circle and stepping into the batter’s box. Why? We were teaching them to think like Manny.

3. When he strikes out or grounds into a double play, Manny immediately puts the failure behind him and moves on. No frustration, no cursing himself or the baseball gods, no wasting emotional energy on “what-ifs.” (Maybe this is why Youk and Manny don’t get along.) Manny just accepts his fate, takes a seat, and starts preparing for his next at-bat. Sometimes his lack of frustration is interpreted as a lack of intensity or competitiveness, but anger just doesn’t work for Manny – and anger and frustration don’t work too well for kids, either. The play is over, now move on in as positive a state of mind as you can. That’s Manny.

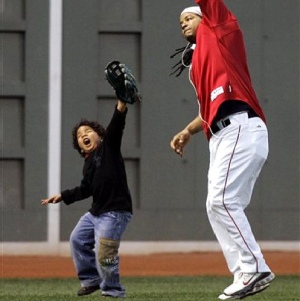

4. Manny plays baseball joyfully. Just about every little league coach in the land tells kids, “Have fun out there!” But do they really mean it? The truth is, it’s simply not O.K. in our U.S. athletic culture to appear to be having fun in certain game situations. Manny is happy all the time, whether the team is winning or losing, whether he’s just hit a grand slam or grounded into a double play, whether he’s benched or facing a 3-2 pitch in a clutch situation, whether the media is writing character-puncturing articles about him or cozying up to him for “being Manny.” As a coach, I really DO want my players to have fun playing baseball, and Manny’s a tremendous role model in this way.

5. Manny works hard in the off-season to get his body ready for spring training. He takes about ten days off after the season ends, then begins a strenuous workout regimen with one of the toughest trainers in the business. All good youth athletics coaches tell their players, “You want to get good? Work hard.” In 2007, The Boston Herald interviewed Seattle’s Raul Ibanez about his off-season workouts with Ramirez in Florida:

5. Manny works hard in the off-season to get his body ready for spring training. He takes about ten days off after the season ends, then begins a strenuous workout regimen with one of the toughest trainers in the business. All good youth athletics coaches tell their players, “You want to get good? Work hard.” In 2007, The Boston Herald interviewed Seattle’s Raul Ibanez about his off-season workouts with Ramirez in Florida:

“In between sets, everything is timed, and he would always be reminding [me] to keep working. He works his tail off. I knew he was hard-working, but he exceeded my expectations. We would start at 10 and he was coming at 9 to do his workouts. He was working out an hour more. He influenced everybody to come in and work out earlier.”

Now is Manny a perfect role model for young baseball players? No. And neither am I, and neither are you. I would tell little leaguers, “Manny does some things badly, and some things exceptionally well. Let’s learn from what he does well.” Over the last decade, the closest MLB has come to a flawless role model has been Ironman Cal Ripken. Great leader, great worker, played hard, played hurt. But to create an ideal role model for young players, I’d want to combine Cal with Manny. Mix Cal’s determination and toughness with Manny’s jubilant, expectant frame of mind, and you have a powerful, positive role model.

My idea about what to DO with Manny (keep him, or trade him?): Pick up his option for 2009 and tell him we’re NOT picking it up for 2010. Get one more productive year out of him at $20M and ensure his self-motivation by guaranteeing him free agency in 2010. I love Manny and don’t want to lose him, but his age (and the physical decline that inevitably comes with age, unless you are Roger Clemens) worries me.