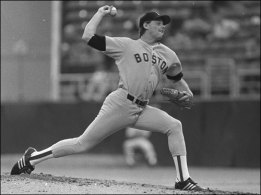

A ticket to a Red Sox game. There’s nothing quite like holding one in your hands. It’s that sublime feeling of knowing a Fenway Park experience lies in your future. The anticipation is palpable. Regardless of whether the Sox eventually win or lose, with a ticket to a game, you’re guaranteed the thrill of watching Big Papi and Manny stride into the on-deck circle; the roar of the crowd following a spectacular defensive play; the majesty of the Green Monster looming in left field; two choruses of Sweet Caroline and its euphoric chant, “So Good! So Good! So Good!” And for many of us, there’s Fenway’s time-capsule quality that transports us back to our childhoods and reconnects us with our parents, or the spirits of our parents who have passed away, and re-ignites in us the joy of being alive.

A ticket to a Red Sox game. There’s nothing quite like holding one in your hands. It’s that sublime feeling of knowing a Fenway Park experience lies in your future. The anticipation is palpable. Regardless of whether the Sox eventually win or lose, with a ticket to a game, you’re guaranteed the thrill of watching Big Papi and Manny stride into the on-deck circle; the roar of the crowd following a spectacular defensive play; the majesty of the Green Monster looming in left field; two choruses of Sweet Caroline and its euphoric chant, “So Good! So Good! So Good!” And for many of us, there’s Fenway’s time-capsule quality that transports us back to our childhoods and reconnects us with our parents, or the spirits of our parents who have passed away, and re-ignites in us the joy of being alive.

And this was all true BEFORE the Red Sox ever won a World Series. Now, when we go to Fenway, we get to see the World Champions!

No wonder it’s so hard to get a ticket. Yes, demand for tickets is through the roof, and the Red Sox continue to price their tickets at levels well below “market value” in order to keep a Fenway Park experience accessible to the “average fan.” In addition, ticket supply is low – we have the smallest stadium in Major League Baseball and 81 home games just isn’t enough to satisfy our fans’ hunger. And as any college professor of economics will tell you, these three forces (along with complete lack of enforcement of scalping laws) make a “secondary market” for tickets inevitable. So that’s what we have in Red Sox Nation: a robust, flourishing, highly profitable  market for Red Sox tickets that have already been sold once by the team.

market for Red Sox tickets that have already been sold once by the team.

Almost nobody loves the ticket reselling (“scalping”) industry. Yet, as I see it, there are only a handful of ways the Red Sox could combat ticket resellers, and almost all of them seem silly:

1) The Sox could price all seats at fair market value. That would mean a “dutch auction” for every ticket, which would lead to prices of at least $500 per seat for every game. Yes, that includes bleachers and standing room only. This would kill the reselling industry’s interest in Sox tickets because, theoretically, no ticket would be sold initially for an amount less than its highest potential bid.

2) The Red Sox could start to lose more games than they win, which would diminish demand.

3) The Red Sox could tear down Fenway and build a stadium with 100,000 seats. This would probably curtail demand (Fenway is an attraction, regardless of how well the team plays) and also increase ticket supply.

4) The Red Sox could petition Major League Baseball to play all their games at home. If they were successful, this would double the supply of tickets. Likewise, they could petition the league to play 50 home games against the Yankees, to make these tickets less special.

5) The Red Sox could revoke all season ticket holders’ seats. Season ticket holders are currently the biggest supplier of the “secondary market” (after all, who has time to attend every home game?) and putting more tickets back under control of the team would take a huge bite out of resellers’ inventory and would allow the Red Sox to find more “unique” fans to sell them to – fans who would be more likely to actually use the tickets rather than resell them.

6) The state of Massachusetts could enforce the law against reselling tickets at more than $2 of their face value. Which, it appears, will never happen.

Short of these drastic measures, however, there are proactive ways to combat the reselling industry and get tickets into the hands of “regular fans,” and the Red Sox use almost all of them. They:

1) Place strict ticket limits on ticket-buying customers (other than season ticket holders) to ensure a large number of “unique” buyers.

2) Hold several “random drawings” before and during the season, which gives lucky fans the right to purchase online highly coveted Green Monster seats, Right Field Roof Deck seats, Yankee Game seats, and even playoff and World Series seats. (I have “won” Red Sox email drawings three times over the years, proving that it really does work.)

3) Host a “scalp-free zone” outside Fenway, which enables fans to sell their tickets at face value on the day of the game. Buyers of these tickets are required to enter Fenway immediately after buying a ticket, to ensure the tickets don’t get resold for a profit.

4) Sell “day of game” tickets at Gate E, beginning two hours before game time.

5) Announce the sale of new blocks of tickets at random times before and during the season.

6) Set technological traps to foil resellers in the online ticket-buying process.

Consider this: By keeping ticket prices well below their actual market value, the Red Sox are effectively offering “financial aid” to every person who buys a ticket directly from them. Absurd, you say? Not really. If the actual value of a particular ticket is $500 on the open market, and the Red Sox know this yet choose to sell this ticket for $80, they are purposefully offering financial aid of $420 to the buyer of that ticket. And they do this for the same reason that Harvard does it, or Andover, or any other expensive educational institution: because they don’t want their customer base to consist solely of wealthy people.

There’s a moral angle here, to be sure, but there’s also a long-term business angle. If the Sox were to maximize their profit now by selling tickets at their actual market value (which would terminate the secondary market for Sox tickets), the economic diversity of their fan base would diminish. Consequently, if the team were to hit hard times in the future (i.e., they begin to lose more games than they win… uncomfortable to imagine, I know), they would have a difficult time selling tickets at the exorbitant prices leftover from the glory days of 2008 and would probably have to slash prices. In addition, attracting back the millions of fans who were disillusioned by their lack of access to games might be a major challenge.

A few days ago, the Red Sox signed a sponsorship agreement with Ace Ticket and proclaimed them “the official ticket reseller of the Boston Red Sox.” Yes, it’s crummy that ANY team has an “official ticket reseller,” but to put in perspective how established the ticket reselling industry is in 2008, keep in mind that Major League Baseball itself has partnered with StubHub, another ticket reseller, as the official ticket reseller of Major League Baseball. The entire LEAGUE is profiting from the ticket reselling industry — it’s not just the Red Sox.

A few days ago, the Red Sox signed a sponsorship agreement with Ace Ticket and proclaimed them “the official ticket reseller of the Boston Red Sox.” Yes, it’s crummy that ANY team has an “official ticket reseller,” but to put in perspective how established the ticket reselling industry is in 2008, keep in mind that Major League Baseball itself has partnered with StubHub, another ticket reseller, as the official ticket reseller of Major League Baseball. The entire LEAGUE is profiting from the ticket reselling industry — it’s not just the Red Sox.

To the Red Sox’ credit, last year they instituted a program called “Red Sox Replay” that enabled season ticket holders to resell their tickets online at virtually face value (fans could log on and buy tickets at a markup of approximately 25%, a small percentage of which went to the Red Sox for maintenance of the site). But the moment MLB inked their exclusive deal with StubHub, the Sox were forced to tear down Replay, since it competed with StubHub’s interests. As Sam Kennedy, the Sox’ chief Marketing and Sales officer, told The Boston Globe earlier this week, without Replay, the Sox felt compelled “to identify and endorse a secure and reputable secondary market option” for their season ticket holders.

It’s also important to point out that the Red Sox have not provided Ace with “tickets for resale” as part of their deal, and the Sox do not stand to profit from a single ticket that Ace sells. This is a straight advertising deal – the team is simply accepting a large check from Ace Ticket for sponsorship (and, we trust, investing this back into the team on the field), and they have sent a letter to their season ticket holders recommending Ace Ticket as the team’s reseller of choice. That’s it.

Now if Abe Lincoln owned the Red Sox, would he have signed a sponsorship agreement with Ace? No. What about A. Bartlett Giamatti, the former commissioner of baseball who was as principled a man as ever lived (he’s the guy who banned Pete Rose from baseball). Would Bart have signed a sponsorship agreement with Ace? Probably not. Abe and Bart would have eschewed any deal that appeared to link their team with scalpers.

Now if Abe Lincoln owned the Red Sox, would he have signed a sponsorship agreement with Ace? No. What about A. Bartlett Giamatti, the former commissioner of baseball who was as principled a man as ever lived (he’s the guy who banned Pete Rose from baseball). Would Bart have signed a sponsorship agreement with Ace? Probably not. Abe and Bart would have eschewed any deal that appeared to link their team with scalpers.

On the other hand, neither of these men were successful businessmen, and neither would ever have been picked to run a major league baseball team. The Red Sox are not only our beloved Olde Towne Team, they are a business. “Good business” helped us win it all in 2004 and 2007, and good business will help us win in the future, as well. It’s hard to fault the business people at the Red Sox for pocketing an easy endorsement check (and offering a “benefit” for season ticket holders) when not doing so would (arguably) jeopardize our competitiveness in the American League East. The money the Sox are making from the Ace Ticket deal will help them put the highest quality team on the field for 2008 and beyond. Yup, winning really does have a steep price.

While down here in Fort Myers, I had a chance to talk about all of this with Ron Bumgarner, Red Sox VP of Ticketing, for about 30 minutes. And what I’ve concluded is that his job is different from that of every other VP of Ticketing at every other MLB franchise. While other teams are busy trying to sell as many tickets as they can at the highest possible prices, the Red Sox are trying to sell all of their tickets at a discount (theoretically) to as many unique, regular fans as is possible, and working assiduously to thwart ticket resellers at the same time (yes, even though they just advised their season ticket holders to sell their unused tickets to Ace, the Sox will continue to try to keep  other individual tickets out of Ace’s and other resellers’ hands). Profit was Ron’s main concern when he ran ticketing for the San Diego Padres, but here at the Red Sox, profit takes a back seat to equitability and wide distribution of tickets across Red Sox Nation’s loyal citizenship.

other individual tickets out of Ace’s and other resellers’ hands). Profit was Ron’s main concern when he ran ticketing for the San Diego Padres, but here at the Red Sox, profit takes a back seat to equitability and wide distribution of tickets across Red Sox Nation’s loyal citizenship.

And you just have to trust me when I tell you that Ron is committed to keeping Fenway accessible to “regular fans.” He has a couple of young children of his own, and I know he relates personally to the “regular fan” whose parents brought him/her to games at Fenway during childhood, and now wants to bring his/her kids to the park, too. “It’s a complicated problem,” Ron told me, “But since it means the Red Sox are winning games, it’s a good problem in the end.” Right?